In the summer of 2015, the Washington Art Association in Washington Depot, Connecticut, held a juried exhibition, The Art of Painting. Serving as adjudicator for the competition was naturalist painter and Kingman Brewster Professor Emeritus of Art at Yale University, William Bailey. Bailey selected two landscape painters — Christopher W. Benson and Russell Horton, both Rhode Island natives — as first-prize co-recipients. Now, the first joint exhibition of paintings by these New England artists, entitled Passerby: Two Easterners Paint the West, is on view at the Museum of the Southwest in Midland, Texas, through February 4.

Most of the 33 works in the show may be read as a circuitous road-trip through the West, from Kansas City to the California Coast. Except for three (incongruous) figurative paintings, all scenes are devoid of human life, though human intervention on the environment proliferates.

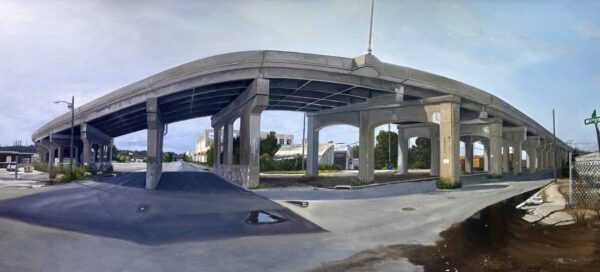

At the easternmost point of our journey in Kansas City, Horton has rendered haunting scenes of urban decay via deserted concrete thoroughfares, as in his Central Avenue Viaduct at North 1st Street. Here, the elevated curve of the overpass, borne aloft by legions of arched piers, recollects an abandoned ancient Roman bath or amphitheater, flanked by the ruins of chain-linked fencing and cracked sidewalks. Though our angled perspective gives us a view of two streets, we see no presence of human or animal life. Just the green of weeds emerging through fractured cement. And though our vantage point does not provide a view of traffic on the viaduct itself, we have the eerie sense that there is none, as if we ourselves were left behind, forgotten, the morning after Armageddon.

As if to provide a peaceful, though no less isolating, antithesis to these unsettling inner-city images, Horton takes us further west, to the Wakarusa Wetlands and the Quivira National Wildlife Refuge (outside Lawrence and north of the Oklahoma Panhandle, respectively). While his Quivira, Northeast 170th Street and Wakarusa Wetlands Pond convey a serene horizontality, and wide, partly cloudy skies are reminiscent of such landscape masters as John Constable or Jacob van Ruisdael, Horton’s Quivira Floodgate disrupts the landscape with the rigid, Charles Sheeler-like insertion of industrial locks. The effect between his scenes is that of a slow fade from urban to rural, like driving out of the city and into the countryside. “The unspoiled vista of American landscape no longer exists” on the Plains, Horton has pointed out, positioning his work as “a critique of nostalgic rhetoric of the pristine.”

Benson picks up the journey where Horton leaves off, taking us further west still, into the Southwest. His views of Black Mesa, in the Pojoaque Valley north of Santa Fe, recall the landscapes of the early 20th century American Modernists, like the structural formalism of Andrew Dasburg set against the lyrical brushwork of Marsden Hartley or John Marin in their New Mexico days. Benson’s scenes of Roswell render the city a ghost town, as in his Duran Corner and his Roswell Number 2. The latter, depicting an Auto Aid the hue of a Tuscan villa, carries hints of Ed Ruscha’s Standard Oil series; but the surrounding vacant streets and agriculture industry warehouses in Benson’s painting produce an atmosphere that is more forlorn than iconic. These New Mexico tableaux are what Edward Hopper would have painted had he, too, ventured west as Horton and Benson did — had he applied the impassive solidity of his lighthouses and gas pumps to the crumbling adobe houses of the rural Southwest.

Installation view of Christopher W. Benson and Russell Horton’s works in “Passerby: Two Easterners Paint the West”

As Benson takes us to the California Coast, his work takes a turn that is decidedly Diebenkorn. We leave the bulky stasis of architecture behind for the dynamic strokes of nature, of sea colliding with rock and sand. The shift in style is a rousing smack following our somnambulist journey through the arid desert. It is the juxtaposition of unrelenting motion against apparent permanence that jars us, making us feel as if we’ve arrived at the end of our journey, when the last thing we remember is staring out the car window at miles of open vista.

Though from New England, both Benson and Horton have lived, for a time, west of the Mississippi: Benson for almost twenty years in Santa Fe, and Horton in Kansas and Missouri. These two artists, along with anyone who has examined a nighttime satellite image of the U.S., recognize the divide that courses between the population-saturated East and the remote (by comparison) vastness of the West. Whether their paintings in Passerby were created in cooperation with one another or discretely, the exhibition reads as a conversation: together, the two artists’ works read as a chronicle of isolation. But Passerby also functions as a record of human incursion into the natural environment, carrying with it a portent of what is lost when built environments encroach upon nature. There is, too, a foreshadowing of a natural world ready to reclaim its own, if left to its own devices.

Passerby: Two Easterners Paint the West is on view at the Museum of the Southwest in Midland through February 4, 2024.